TLDR (Too Long, Didn’t Read)

- The Qur’an does not prohibit prayer based on substances, but based on mental state

- The key Qur’anic rule is: do not pray if you do not know what you are saying

- Alcohol reliably violates this standard, which is why it is treated strictly

- Cannabis is variable, dose-dependent, and user-dependent

- Some Muslims report that low or controlled cannabis use does not impair comprehension or prayer

- Islamic law historically judges intellect, discernment, and presence, not chemistry

- Prayer is invalid if awareness, memory, recitation, or reverence are compromised

- The real question is state of mind, not the plant itself

- This is a legitimate scholarly discussion, not a modern loophole

Introduction

As cannabis becomes more socially accepted and legally accessible in many parts of the world, Muslim communities are increasingly forced to confront questions that were once marginal or hypothetical. Among these questions, few are as sensitive as whether cannabis use interferes with the validity of prayer.

The issue is often framed in simplistic terms. Cannabis is compared directly to alcohol, alcohol is known to be forbidden, and therefore cannabis must follow the same ruling. This framing is intuitive, but it rests on assumptions that deserve closer scrutiny.

Islamic law has never functioned purely by surface analogy. Its rulings emerge from careful attention to text, purpose, human capacity, and lived reality. When examined through this lens, the relationship between cannabis and prayer becomes far more nuanced.

This article does not attempt to normalize cannabis use or dismiss scholarly caution. Instead, it seeks to clarify what the Qur’an actually requires for prayer, how Islamic law understands intoxication, and why some Muslims argue that a minor or controlled cannabis state does not automatically invalidate worship.

1. The Qur’anic Threshold for Prayer Is Cognitive, Not Chemical

The cornerstone of this discussion is a single verse from the Qur’an:

“Do not approach prayer while you are intoxicated until you know what you are saying.”

This verse does something subtle but profound. It defines intoxication by its effect, not by its cause. The problem is not ingestion, but incapacity. The condition for prayer is restored not by waiting a set amount of time, but by regaining understanding.

This framing matters because it tells us how the Qur’an conceptualizes worship. Prayer is not merely a physical ritual. It is an intentional, conscious act of communication. If that communicative capacity is compromised, prayer loses its meaning.

Importantly, the verse does not outlaw altered states in general. It does not demand a pristine or untouched mind. It demands functional comprehension.

This distinction underlies nearly every disagreement that follows.

2. Alcohol’s Special Status Comes From Reliability, Not Symbolism

Alcohol occupies a uniquely severe position in Islamic law because it consistently and predictably undermines cognition. Its effects are not subtle, rare, or context dependent. Alcohol consumption commonly leads to confusion, loss of inhibition, impaired memory, and reduced self control.

From the standpoint of prayer, alcohol almost always violates the Qur’anic threshold. It makes it difficult or impossible to speak intentionally, to remember sequences, or to maintain reverence. Because of this reliability, alcohol became the legal baseline for intoxication.

This is an important clarification. Alcohol is not treated harshly because it is foreign, sinful, or morally distasteful. It is treated harshly because it reliably damages the very faculties prayer depends on.

Later jurists extended alcohol’s ruling to other substances by analogy, but analogy is only as strong as similarity of effect.

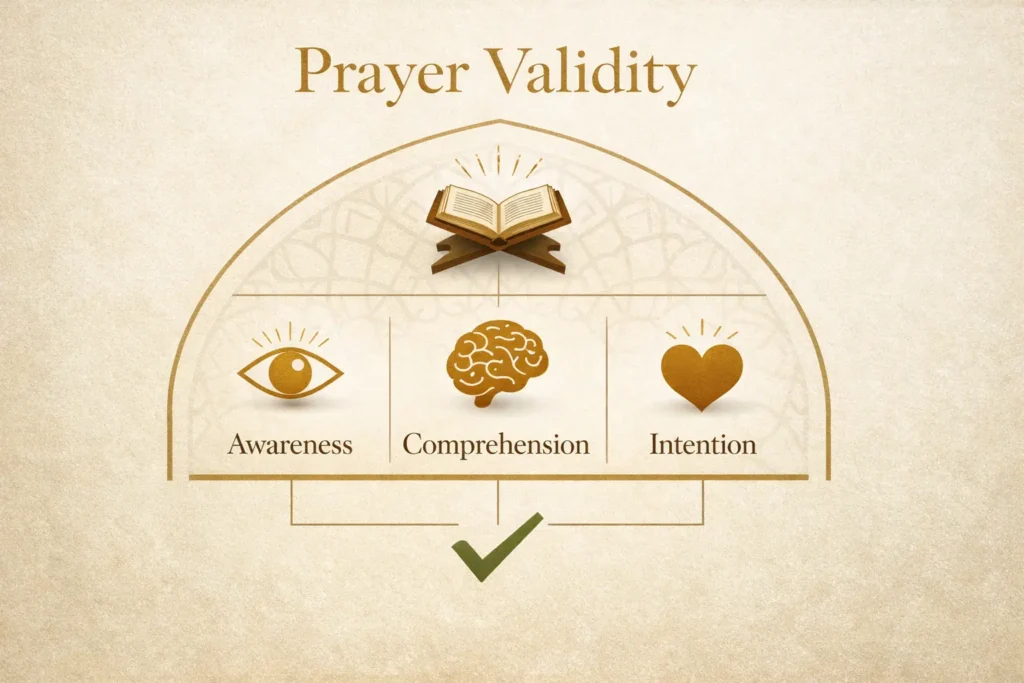

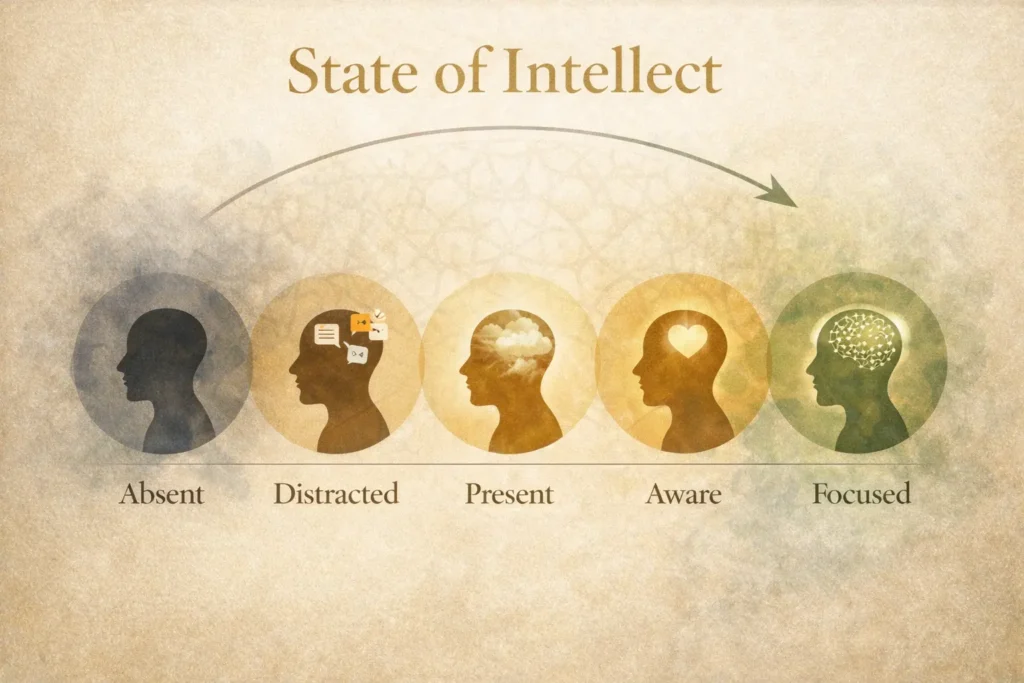

3. Islamic Law Evaluates the State of the Intellect

Classical Islamic jurisprudence is deeply concerned with the state of the intellect. Legal accountability, worship obligations, and moral responsibility all hinge on a person’s capacity to understand, intend, and choose.

This is why Islamic law already recognizes that prayer can be compromised by non chemical factors. Severe exhaustion, psychological dissociation, extreme emotional distress, or overwhelming distraction can all interfere with prayer if they eliminate awareness or intention.

At the same time, many accepted influences clearly alter mental state without invalidating prayer. Caffeine stimulates attention. Prescription medications regulate anxiety or focus. Pain management dulls sensation. These are not seen as violations because they do not necessarily remove comprehension.

The consistent pattern is this: Islam does not require an untouched mind, but a functioning one.

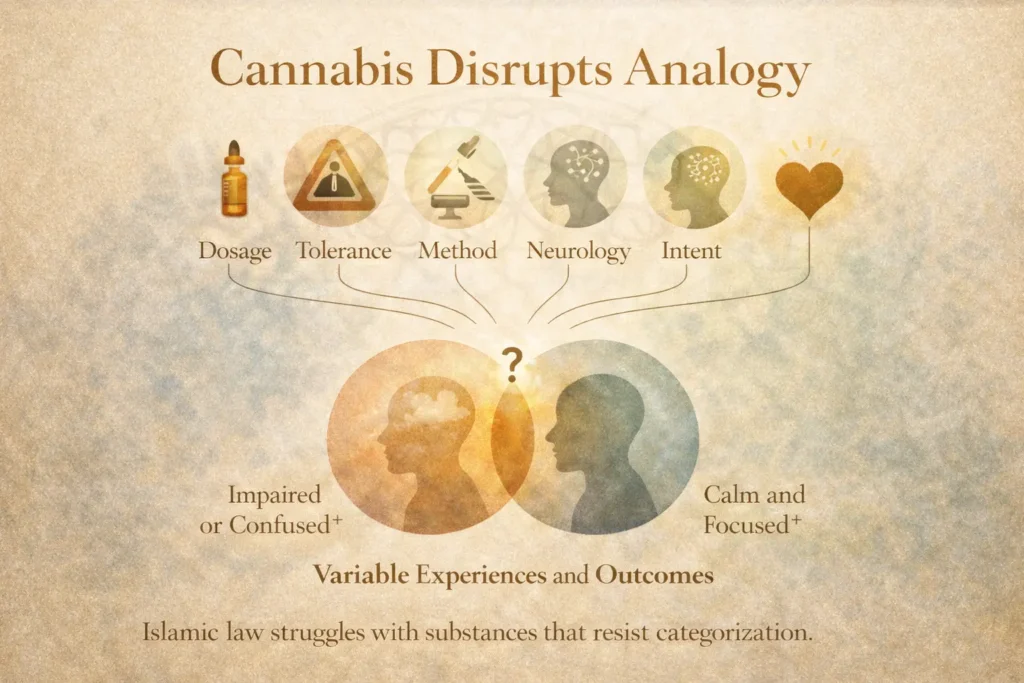

4. Cannabis Disrupts Analogy Because It Is Not Uniform

Cannabis presents a challenge precisely because it does not behave consistently across users or contexts. Its effects vary widely depending on dose, tolerance, method of consumption, neurological makeup, and intent.

For some users, cannabis causes impairment or confusion. For others, particularly at low doses, it produces calm, focus, or sensory regulation. These differences are not anecdotal anomalies. They are well documented and widely acknowledged.

Islamic law struggles with substances that resist categorization because the law prefers predictable outcomes. Cannabis does not reliably produce the same state in every user, which makes blanket rulings difficult to justify on purely functional grounds.

This is why scholarly responses vary. Some emphasize caution and prohibition. Others distinguish between intoxicating and non intoxicating use. Still others approach cannabis through the lens of medication rather than vice.

The disagreement is not evidence of laxity. It is evidence of a substance that defies easy classification.

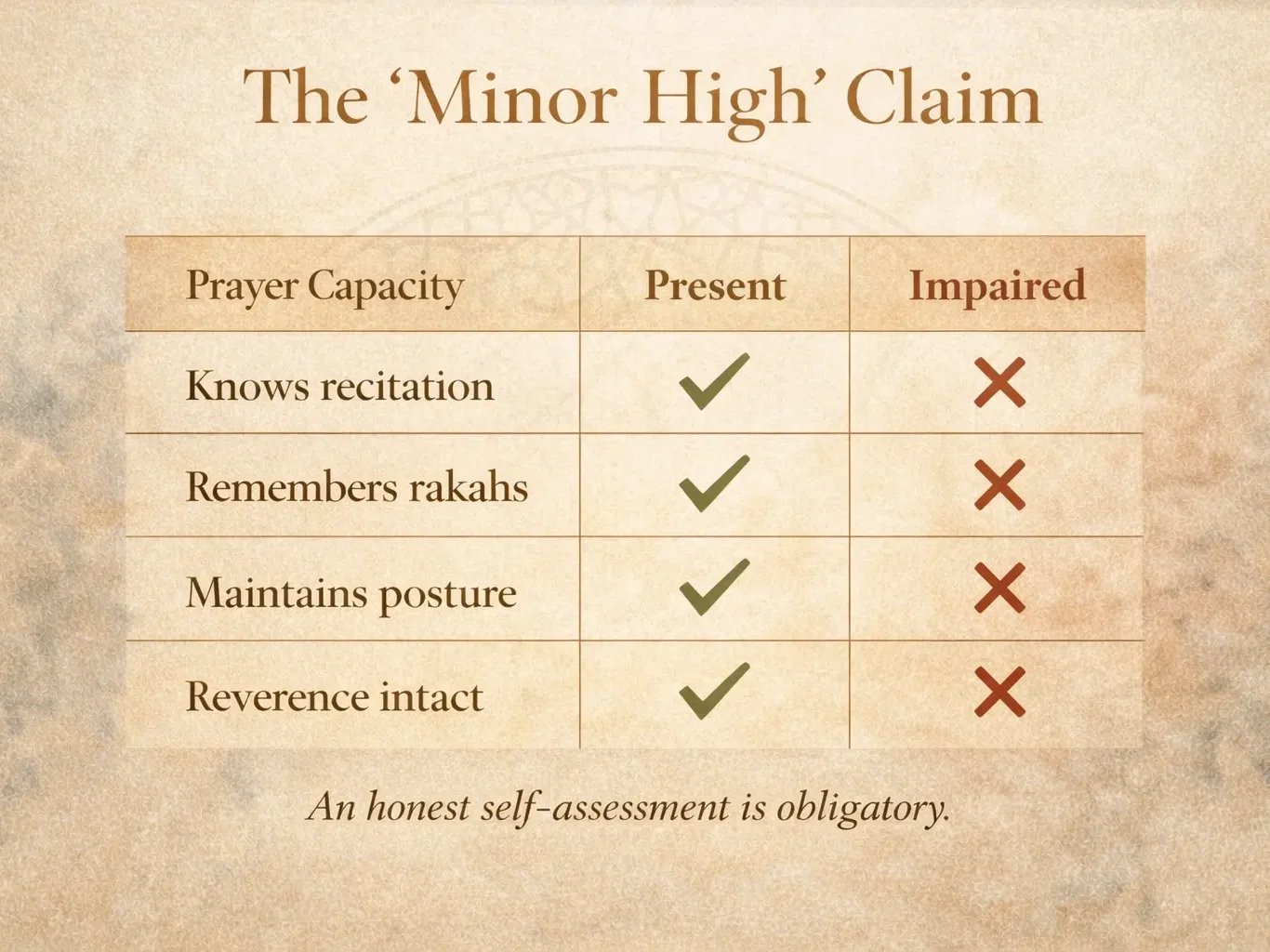

5. Understanding the Claim That Cannabis Does Not Affect Prayer

When Muslims who use cannabis say that it does not interfere with their prayer, they are often misunderstood. They are not claiming exemption from Islamic law, nor are they redefining prayer standards.

They are making a narrower claim: that their cognitive and linguistic faculties remain intact.

They report understanding their recitation, maintaining awareness of posture and sequence, remembering rakahs, and experiencing intentional presence. In their assessment, they meet the Qur’anic condition of knowing what they are saying.

Whether one agrees with this assessment is a separate question. What matters is that the claim is state based, not ideological. It is grounded in experience rather than theory.

Islamic law has always required individuals to assess their own capacity honestly. This claim lives or dies by sincerity, not argument.

6. Khushu, Presence, and a Tension Already Within Prayer

Islamic tradition places immense value on khushu, the inward state of humility and attentiveness during prayer. While legal validity and spiritual quality are distinct, they are not unrelated.

In reality, many prayers are performed in states of distraction, stress, or emotional fragmentation. These prayers may be legally valid, but they are spiritually diminished.

Cannabis introduces an uncomfortable question rather than creating a new problem. If a person is sober but mentally absent, is that state inherently superior to one of calm focus and intentional presence? Islamic law does not give a simple answer.

What it does emphasize is sincerity, discipline, and avoidance of dependence. Any aid that replaces effort or becomes a crutch is suspect. Yet presence itself is never dismissed as irrelevant.

This tension already exists in prayer practice. Cannabis simply exposes it more clearly.

7. Where Boundaries Must Be Drawn

Even within the most permissive interpretations, certain lines cannot be crossed. Prayer is compromised if cannabis use results in delayed prayer times, impaired recitation, forgotten movements, loss of reverence, or reliance on the substance to access worship.

Islam is deeply concerned with accountability. Any state that undermines responsibility, intention, or humility violates the spirit of worship, regardless of its source.

Self honesty is essential. If a person claims clarity while actually experiencing impairment, the problem is not the substance, but the deception.

8. What This Article Argues and What It Refuses to Argue

the Qur’anic rule governing prayer is functional rather than chemical.

This article does not declare cannabis permissible. It does not deny the legitimacy of scholarly caution. It does not encourage altered states as spiritually superior.

It does argue that the Qur’anic rule governing prayer is functional rather than chemical. It shows that Islamic law historically evaluates mental state rather than substances in isolation. It explains why cannabis complicates alcohol based analogies and why the debate persists.

Most importantly, it insists that this conversation is not a modern excuse or a dismissal of Islam. It is a serious engagement with revelation, law, and human experience.

Conclusion

The question of praying while high cannot be answered by analogy alone. Alcohol and cannabis differ in history, text, and effect. The Qur’an defines intoxication by comprehension, not consumption. Islamic law prioritizes discernment and presence over chemical categories.

This does not eliminate caution. It demands greater responsibility.

The ultimate question Islam asks is not what entered the body, but whether the worshipper stands before God knowing what they are saying.

That question cannot be resolved by slogans. It must be answered through sincerity, humility, and honest self assessment.

Scholarly Sources, Legal Foundations, and Further Reading

This article draws on established principles of Islamic jurisprudence, Qur’anic exegesis, historical scholarship, and contemporary ethical discussion. While no single source resolves the question definitively, the following materials help contextualize the debate and demonstrate that it is grounded in serious intellectual tradition.

Primary Qur’anic Foundations

The discussion of prayer and intoxication centers on the Qur’anic framing of comprehension and awareness.

- Qur’an 4:43

Establishes the functional condition for prayer by tying prohibition to understanding rather than ingestion. - Qur’an 5:90–91

Provides the moral and social rationale for prohibiting intoxicants, emphasizing harm, discord, and disruption of worship.

These verses form the textual anchor for all later legal reasoning.

Classical Islamic Legal Principles Referenced

The following legal maxims and concepts are foundational across schools of Islamic jurisprudence and are relevant to the discussion of mental state, worship, and accountability:

- Al-Umur bi Maqasidiha

Actions are judged by their intentions. - Al-Asl fi al-Ashya al-Ibaha

The default ruling of things is permissibility unless clearly prohibited. - Al-Darar Yuzal

Harm must be removed. - Tamyiz and Aql

Discernment and intellect as prerequisites for accountability and worship.

These principles are discussed extensively in classical usul al-fiqh literature.

Classical Scholars and Texts Engaging Intoxication and Intellect

While cannabis itself is not directly addressed in the Qur’an, substances such as hashish were known and debated in premodern Islamic societies.

Recommended classical references include:

- Majmu al-Fatawa by Ibn Taymiyyah

Distinguishes between wine and other substances and emphasizes the role of intellect rather than form. - Al-Furuq by Al-Qarafi

Explores legal distinctions between similar cases and warns against careless analogy. - Tafsir al-Kabir

Discusses the meaning of sukr and its relationship to loss of understanding. - Tuhfat al-Muhtaj

Addresses non wine intoxicants and differentiates levels of impairment.

These works show that historical scholarship did not treat all intoxicating substances as identical.

Modern Academic and Historical Studies

Several modern scholars have examined intoxicants in Islamic societies with attention to nuance rather than assumption.

Recommended academic works include:

- The Herb: Hashish versus Medieval Muslim Society

A foundational historical study showing how hashish was debated, regulated, and socially understood. - Intoxicants in Islamic Law

Explores how jurists navigated substances not explicitly named in revelation. - Alcohol and Hashish in Medieval Egypt

Examines political, social, and legal responses to intoxicants in Islamic history.

These sources demonstrate that the relationship between Islam and intoxicants has never been monolithic.

Contemporary Fiqh Councils and Ethical Discussions

Modern Islamic institutions have addressed psychoactive substances primarily in medical and ethical contexts.

Relevant bodies and discussions include:

- International Islamic Fiqh Academy

Rulings on medical narcotics and necessity based exceptions. - European Council for Fatwa and Research

Statements permitting controlled medical use of psychoactive substances under necessity. - Islamic medical ethics programs at universities such as IIUM and University of Jordan

Research on cannabinoids, mental health, and treatment ethics.

While these bodies often err on the side of caution, they acknowledge distinctions between intoxication, treatment, and impairment.

Related Topics for Further Exploration

Readers interested in deeper engagement may explore adjacent topics that illuminate the broader framework:

- Khushu and the psychology of prayer

- Mental health, medication, and worship

- Sobriety versus presence in Islamic spirituality

- Addiction, dependence, and spiritual discipline

- Intention and accountability in altered states

- Legal versus spiritual validity in acts of worship

Each of these areas intersects with the cannabis and prayer discussion without reducing it to a single substance.

A Final Note on Method

Islamic law has always balanced text, reason, experience, and humility. Disagreement does not signal weakness. It signals engagement.

Readers are encouraged to approach this topic not with the goal of winning an argument, but with the intention of understanding the principles that govern worship, responsibility, and sincerity.